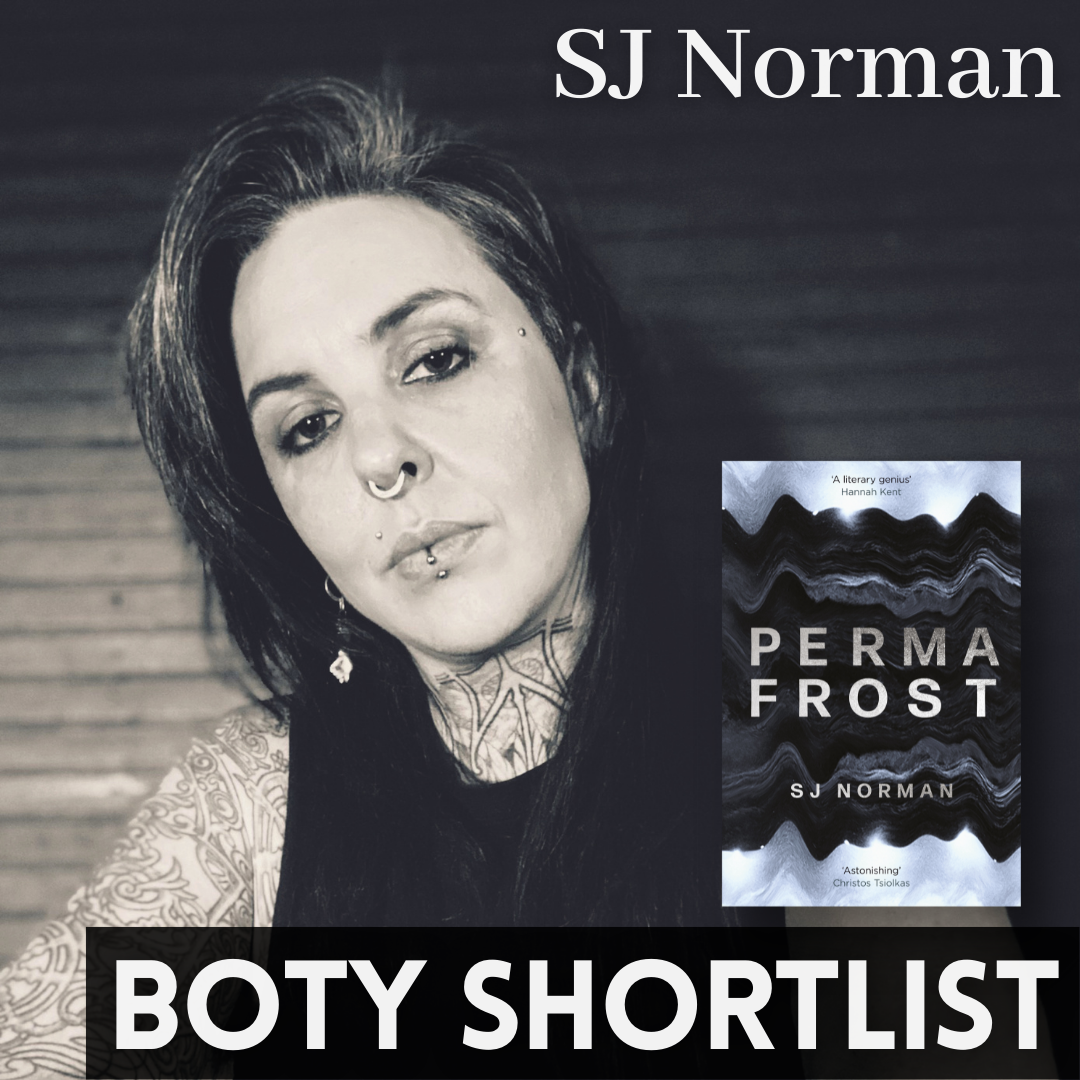

In conversation with BOTY shortlisted author SJ Norman

‘Permafrost (UQP) is a collection of stories that delve into uncomfortable spaces that lie beneath familiar experiences of travel, love and loss. SJ Norman’s work presents an exciting, unsettling and engaging new voice that explores the human diasporic experience, bringing a queer and unique take on the gothic romantic tradition.’

—BOTY 2022 judging panel

We asked SJ some questions about their book Permafrost, one of the shortlisted titles for the 2022 SPN Book of the Year Award. The award ceremony will take place on 25 November, and will feature readings from SJ and the other shortlisted authors.

To see the full shortlist, click here.

To book a ticket to the BOTY award ceremony, click here. All the shortlisted books will be available for purchase at the Independent Publishing Conference and at the BOTY award ceremony, through our conference bookseller, Readings. They can also be ordered through the Readings website.

Q: Which story was the hardest to write? Which one was the easiest?

A: ‘Playback’ was the hardest to write. The challenge with ‘Playback’ had a lot to do with the material—I was drawing on a range of very difficult personal experiences, and processing some very raw and private grief through that story. This made it hard to wrangle. I started writing ‘Playback’ in 2017, which was more than 10 years after I completed the previous story, ‘Stepmother’.

After completing all the other stories in the collection in my late teens and early 20s, I took a very long break from writing—I had sort of abandoned the craft. For that decade I was living in Berlin and focused on other things, and I started ‘Playback’ when I came back to Australia in 2017. It was a homecoming story both in terms of the narrative and the process—a homecoming for me and for that character in terms of place, but also a return to writing as a practice and a way of being. It took two years for me to finish that story, and I hated it passionately the whole time I was writing it. I’m very proud of it now, though. ‘Stepmother’ was the easiest to write and it shows. It’s the shortest, and the least tricksy, and the most polished in terms of craft. I wrote it when I was 24 and really very dedicated and disciplined at that time—I came in with all the chutzpah of a very young writer who was also fighting condition.

Q: Sometimes story ideas can occur to a writer in strange ways, or the writing process can take you in directions you didn’t expect. Did you have any experiences like that with the stories in Permafrost?

A: I never start a story with the faintest clue of where it’s heading. As a visual artist, performer and curator I am extremely methodical—I build a piece of work to function as a beautiful and refined system, with just enough room for some animating chaos to enter. As a storyteller, I’m the opposite. I do usually start with fragments of something—an existing artefact of folklore, some little yarn I’ve heard, or even a film or a song. And I do usually have a set of quite strict formal restraints that I set for myself—in the case of Permafrost, almost every story is first-person/present-tense—but beyond that I don’t really outline anything. I am completely blindfolded from start to finish, and when I step outside of a finished story I can scarcely believe I wrote it. So it’s all strange. It all comes through my hands and eyes and it’s my voice and viewpoint that provides the container, but a story will do what it is going to do, and it is never what I expect. My job is to show up and listen and mediate and figure out what needs to go on the page.

Q: Paranormal incidents are a focal point in this collection. Have you ever experienced anything in real life that felt almost paranormal?

A: All the time. Most of the spooky things that happen in the book are based on things that have happened to me, or to people close to me who have given permission for me to use them in fiction. Not everything is up for grabs though: there are plenty of other personal experiences that I could draw upon but choose not to—mostly because they are of a specific nature and are not for me to retell. For some readers the ghosts are metaphors, and others see them as contemporary folklore, and both of those things are also true. They are also really real ghosts, who mostly behave like real ghosts, which is why the stories don’t tie up neatly the way literary ghost stories usually do—that’s not how real-life hauntings play out. Real-life hauntings are mostly subtle, repetitive and banal, and they are never resolved, and that’s the whole point for me.

Q: Your creative practice extends to other media beyond writing. Do you ever explore what feels like the same story in different forms of art? Is it always clear to you when an idea is a story idea versus an idea to be explored in a different art form, or does that sometimes need to be teased out through trial and error?

A: There is thematic overlap for sure, but they are distinct spaces for me. My work in performance comes from a methodology which is anti-narrative, anti-image, anti-spectacle. My performance work is all about relationality between bodies in space and the histories they carry. My writing touches on similar preoccupations, but I work with it in a completely different way.

Q: This collection has been described as Gothic or having Gothic elements. (The blurb on the back uses the phrase ‘queering the Gothic’.) Do you think of your own work as (intentionally) Gothic, or as being in conversation with the Gothic?

A: The book is in many respects a genre study: I spent a long time studying the tropes of the Gothic as well as the tropes of folkloric storytelling across a lot of different cultural and literary traditions. I have a set of known conventions I am working with and the story sometimes works with the grain of those tropes, and sometimes against it. It’s a kind of call and response between the conventions of those forms as I have studied them and my own riffs and queerings of them. It’s a playful sort of antagonism.

Q: Your stories have such a powerful sense of place. Can you talk a bit about the way you use settings? (e.g. Do you only write about places you’ve visited yourself? Do you ever come up with a setting first and a plot after? Do place and plot sometimes seem to arrive hand in hand?)

A: I guess the stories have a strong sense of place because I have a strong sense of place, and this is just the basis of my approach. This is just an ingrained cultural sensibility for me. All human and more-than-human relations happen in relationship to place, because places are sentient. Land is sentient, but so are cities—if a story takes place in Berlin, then Berlin itself is already a character, not a backdrop. If it happens in regional Australia, then I write that place as a living entity, because it is.

Q: Speaking of places, your characters all seem to experience hauntings while they’re travelling, or revisiting a place they left long ago. They’re never settled, always restless, often waiting for something or caught in between phases of their lives. It gives the collection a strong sense of liminality, which I really enjoyed … I thought I was building up to a question here, but I now realise I don’t actually have one. I guess this is just something I loved about the collection and wanted to mention!

A: I guess I fundamentally relate to liminal and unsettled characters because that’s been such a feature of my own life: I grew up moving around a lot, and from the age of 19 onwards I was always bi-located between different places: I moved to Japan when I was very young to train with a dance company there, and spent a lot of time in a city in Hokkaido where the title story is set, and following that I moved to the UK where I lived in a small town in the West Country where ‘Whitehart’ was set. Following that, I came back to Sydney for about a year before moving again to Berlin, where I ended up living for the better part of 11 years. Now I’m living mostly in New York but back and forth between here and Sydney. I’ve always been coming and going—that’s just been the practical condition of my life as an Aboriginal person, as a queer and as an artist, who always retains an anchor and a sense of relational belonging in Australia, but who also needed to get out for a range of reasons related to my own creative and personal path in life. So in the simplest terms, the stories reflect that. But I am also interested, more formally, in how different places and cultural landscapes are haunted, what conventions those stories take, and how both of those things are formed and activated by history and land. It’s also true that spooky stuff often happens in the in-between: those bleary, dissociative moments on a long journey, either through physical or psychic space, where we might be momentarily estranged from the inner noise of our own selves and ego-processes long enough to expand our field of perception to non-ordinary and non-physical worlds.

Q: What led you to choose ‘Permafrost’ as the title story?

A: It was an intuitive choice. All the titles are double-words, all of them are a both-neither, all of them are about thresholds and collisions. That story was the first story I wrote of all the stories in the collection and probably set the tone for the rest as they unfolded, so that just felt right.

Q: Many of your stories have open endings, or occurrences that are left open to interpretation. Do you have a clearer picture of what happens in these scenes that you simply prefer to keep to yourself, or is the story also unresolved in your head?

A: I know exactly what is happening in all of them. For me, every one of the stories comes to a satisfying conclusion, and they finish exactly where they need to finish. The clues are all there in the symbolism, but I do believe the most powerful and enduring treatments of the uncanny leave a lot of space for a multitude of interpetations and re-interpretaions. Imagine if there was unified consensus about exactly what the hell happened at the end of Twin Peaks, or in any of Banana Yoshimoto’s stories, for instance. How claustrophic and how boring, and what an insult to the spirits themselves, to ask them to behave so politely.

Q: All of your stories are told in the first person by an unnamed narrator. I really liked this touch—I found that it subtly accentuated the sense of unease. Was that a purposeful choice, or is this simply a way of storytelling that comes naturally to you? Do you ever write in the third person or other perspectives?

A: It was a deliberate choice. All of the stories are first person, and in almost all cases, present tense. ‘Playback’, ‘Stepmother’ and ‘Whitehart’ are the only ones that break the present-tense form, and that was again an intentional move that served the story. The unnamed narrators have led some readers to assume the book is autofictional, that each one of the stories is happening to the same person and that person is always a version of me. That’s a tricky one on an meta-analytical level, because every single narrator is always a version of the author and every work of fiction is to an extent an autobiography. But I can say categorically that they are all works of fiction, and all the narrators are distinct and different people to me—I just choose not to signpost those differentiations in a way that renders them clearly legible. This is because I wanted to write stories with an experiential immediacy—I wanted a reader to be able to crawl inside the experience of the story and have it happen to them, moment to moment, and see through the eyes of that character. This is also a queer methodology for me: I am really wanting to resist the onus of representation that is put on trans storytellers, Blak storytellers, and queer storytellers, and move rather in the terrain of affect and gesture and sense-perception. I didn’t want to signpost the identities of the narrators, though they are all also subtly coded to reveal aspects of who they are, to readers who share those identities. It’s stealthcraft to a certain extent, which is itself a queer artform.

Q: When you feel like you’re all out of ideas, where do you seek inspiration?

A: I don’t tend to go actively looking for ideas, I just pay attention to what themes are arising in me with urgency, whatever might be burning in my gut or otherwise activating me, then stay attuned to clues or images or input from the world that might provide a trigger to unlock the story in it. Or sometimes, I’ll riff off other texts—if I read something that has a particular potency for me, then I will sit with why that is, then start modelling something of my own off specific elements, and see what emerges. ‘Stepmother’, for instance, was initially modelled on an Isaac Bashevis Singer story—the finished story retains no resemblance at all to the piece that inspired it, but it provided a jumping-off point. ‘Hinterhaus’ was modelled, initially, on an ETA Hoffmann story, which in turn references German folklore, and ‘Whitehart’ weaves together an accumulation of lore that belongs to the British Isles. Other stories are much more wily, based either on real events (‘Unspeakable’, for instance, is non-fiction, that one is a beat by beat recollection of things that really happened) or on very loose threads of impressions and memories or general moods that weave together and give rise to images which belong to that story alone.

Q: Are you working on anything right now that you’d like people to know about (be it writing, another form of art, or a different kind of project entirely)?

A: I’m working on a tonne of things across a few different mediums. Art stuff keeps going and keeps paying my bills—I have a few shows coming up in various places. I’m also the co-curator of Knowledge of Wounds, an Indigenous-led, queer/trans/2S-focused presenting platform, which I started in 2019 with my collaborator, Joseph M. Pierce, to give Indigenous weirdos making strange art a place to show their work.

I’m working on the treatment of a feature film screenplay, the working title of which is Bloodwood, which will be a queered and Indigenised adaptation of Wuthering Heights set in regional Australia in the 1990s—definitely the campiest and most ridiculous thing I have done, which, like Permafrost, will hopefully be great fodder for Geriatric Millennial queers. That will be directed by Sam Icklow, a close friend and director whom I have worked with once on a short film called ‘The Moth’, which was an adaptation of ‘Hinterhaus’. I also performed in that film, one of my select few acting credits.

I have a new book coming out with UQP next year, Blood from a Stone, which is a book-length verse novel, formally a bit of a tribute to an important early influence, the late Dorothy Porter, which is an auto-fictional reflection of the complexity of gendered violence in the colony.

I’m also working on a non-fiction book, what I am calling my ‘big sad Tr*nny memoir’ which is a book about trans and queer love and eroticism told by/through my transitioning body. I also started work on a novella, which I don’t have a title for yet, which is a light, funny, squishy little story of a May–December romance between a gay cis man in his 50s and a much younger trans man, set in Berlin.

SJ Norman is an artist, writer and curator. Their career has so far spanned seventeen years and has embraced a diversity of disciplines, including solo and ensemble performance, installation, sculpture, text, video and sound. Their work has been commissioned by the Biennale of Sydney, Performance Space New York, Venice International Performance Art Week, and the National Gallery of Australia, to name a few. They are the recipient of numerous awards for contemporary art, including a Sidney Myer Creative Fellowship and an Australia Council Fellowship. Their writing has won or placed in numerous prizes, including the Kill Your Darlings Unpublished Manuscript Award, the Peter Blazey Award, the Judith Wright Prize and the ABR Elizabeth Jolley Short Story Prize. In 2019, they established Knowledge of Wounds, a global gathering of queer First Nations artists, which they co-curate with Joseph M. Pierce. In 2022, their debut book and short story collection, Permafrost, was shortlisted for the 2022 ALS Gold Medal and longlisted for the Stella Prize. They are currently based between Sydney and New York.