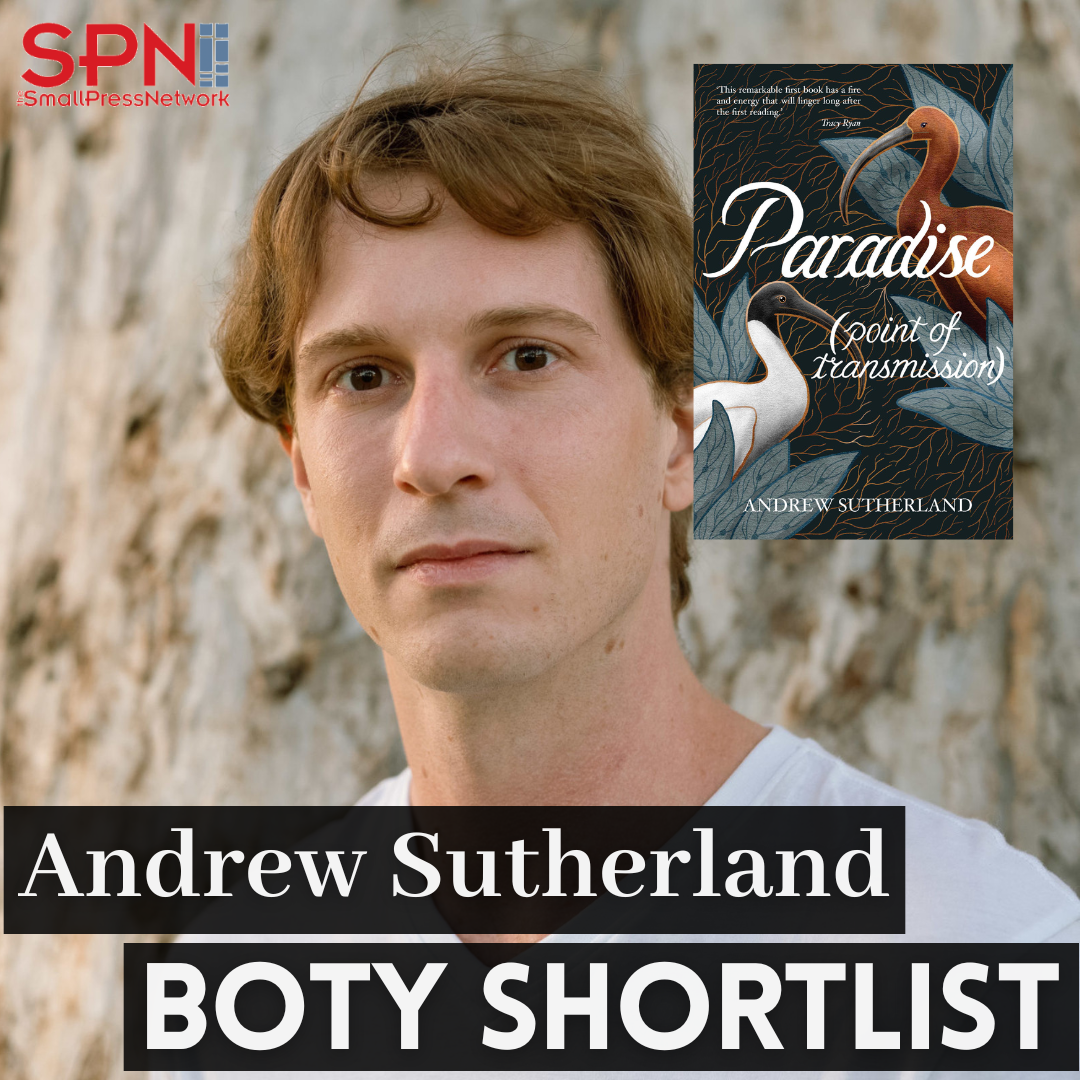

In conversation with BOTY shortlisted author Andrew Sutherland

Paradise (Point of Transmission) (Fremantle Press) is beautifully layered collection of poems that explores the realities of a HIV diagnosis on home, community and freedom. It complex but inviting, an act of generosity and transformation. In his first poetry collection Andrew Sutherland simultaneously captures the stigma of a HIV-positive identity and the deep love of Queer community. This collection is thoughtfully constructed on the page, divided into three sections – narrative, metaphor and paradise, dipping easily between poetics and the domestic. It is a collection that speaks to the poetics of people and life, drawing on theory easily but not arrogantly, and inviting engagement without prior knowledge, but holding deep space for shared experience.

—BOTY 2023 judging panel

We were lucky enough to chat with Andrew about Paradise (point of transmission), one of the shortlisted titles for the 2023 SPN Book of the Year Award.

To see the full shortlist, click here.

Q. Your poems often play with things like space and symbols. How does the visual form of your poems on the page manifest?

Fairly intuitively; I tend to try to think of rhythm, sound and shape on the page in a collapsed kind of way rather than in application of a particular poetic form. So in thinking about whether something is free verse or a prose poem, where does space on the page manifest, where line breaks function, I am tending to try to act as intuitively as possible based on what it seems like the poem or subject needs in order to communicate. And then try to justify that set of choices to myself afterwards – and if it’s not working for me: restructure, reshape, experiment.

Q. The section titled ‘narrative’ has themes of mythology and religion. What is the connection to these themes for you?

I think for me there are certain cultural touchstones, of which a Judaeo-Christian Anglican background is one and of which a childhood fascination with Nordic mythology is another – but this would also apply to cultural properties like, for instance, Buffy the Vampire Slayer – that I am aware suffuse my development and my interest in story and symbol, and to a certain degree these stories tend to structure themselves around the apocalyptic. And when I was diagnosed, it similarly felt apocalyptic and like the end of the life I knew, and it took a lot of mental reorganisation to think about what cultural symbols had encouraged me to think that way. So the organisation of many of these poems in the first section of the book, which structures itself around reiterations of seroconversion and diagnosis, was a way of nodding to those feelings and then moving on. Similarly, there is a sequence of poetry in the ‘narrative’ section which organises itself around signifiers from Nordic mythology and this is a nod to a play that I wrote and had staged when I was fresh out of drama school, called Ragnarok – also coincidentally at the time of my diagnosis. I looked back and was not happy with the personal politics of the play I had written, in relation to HIV or to my own diagnosis. And this sequence of poems was effectively culled from the text of that play – so in some ways, it was a way of salvaging or reconstituting past work into a form that I felt I could stand by.

Q. Historically, a lot of literature on the topic HIV has been centred around the idea of tragedy. Do you think this is changing?

I am not sure that this is necessarily changing in the mainstream sense; I think, as writers like Dion Kagan and Avram Finkelstein have pointed out, the late 200s and 2010s witnessed the solidification of cultural memory around HIV/AIDS, and so the majority of works produced in the mainstream deal with HIV/AIDS in a nostalgist way. It is very easy to apply the form of tragedy to something treated as a past event. So I think that we are much more likely to see works of fiction in the mainstream that are either ‘nostalgist’ in their conception, like the recent television series It’s a Sin, or remounts of so-called ‘crisis era’ media – you would be more likely to see a play like The Normal Heart produced in a mainstream theatre setting than a new work produced that engaged with the continuous existence of HIV/AIDS. There are obviously exceptions to this in our literary and arts sphere but I think culturally, it is difficult to speak about HIV without the listener having already formed a narrative of tragedy in their mind.

Q. I really enjoyed the inclusion of references to sci-fi, vampires and horror. What do you think is the role of these elements in Paradise (point of transmission)?

I am a longterm obsessive over what you’d call ‘cult’ television but also great works of horror and science fiction, because I think that the concepts contained within can be so complex and so truthful in a way that skews into the most powerful, interesting form of Camp, or strangest form of personal recognition. And something that I would contend is that through a certain lens, we might recognise more about the personal experience of living with HIV by watching Interview with the Vampire or by the seventh rewatch of The Exorcist, etc., than we might by watching Philadelphia or Holding the Man. Not that those films or texts aren’t worthwhile – but we should have the opportunity to recognise ourselves through excess, through weirdness, through the world-bending drama of the Camp and the horrific. So that’s why those are there: because I recognise myself in them.

Andrew Sutherland (he/they) is a Queer poz (PLHIV) writer and performance-maker creating work between Boorloo, Western Australia and Singapore. His work draws upon intercultural and Queer critical theories, and the viral instabilities of identity, pop culture and the autobiographical self. As a performance-maker, he has twice been awarded WA’s Blaz Award for New Writing and makes up one half of independent theatre outfit Squid Vicious (@squidvicioustheatre). His recent performance works include 30 Day Free Trial, Poorly Drawn Shark, Jiangshi, Unveiling: Gay Sex for Endtimes and a line could be crossed and you would slowly cease to be, which was commissioned by Singapore’s Intercultural Theatre Institute in 2019. As a poet, he was awarded Overland’s Fair Australia Poetry Prize 2017 and placed third in FAWWA’s Tom Collins Prize 2021. His poetry, fiction and non-fiction can be found in a raft of national and international literary journals and anthologies, including Cordite, Westerly, Portside Review, 聲韻詩刊 Voice & Verse, EXHALE: an anthology of Queer voices from Singapore, and Margaret River Press’ We’ll Stand in That Place, having been shortlisted for their 2019 Short Story Prize. He is grateful to reside on Whadjuk Noongar boodja.