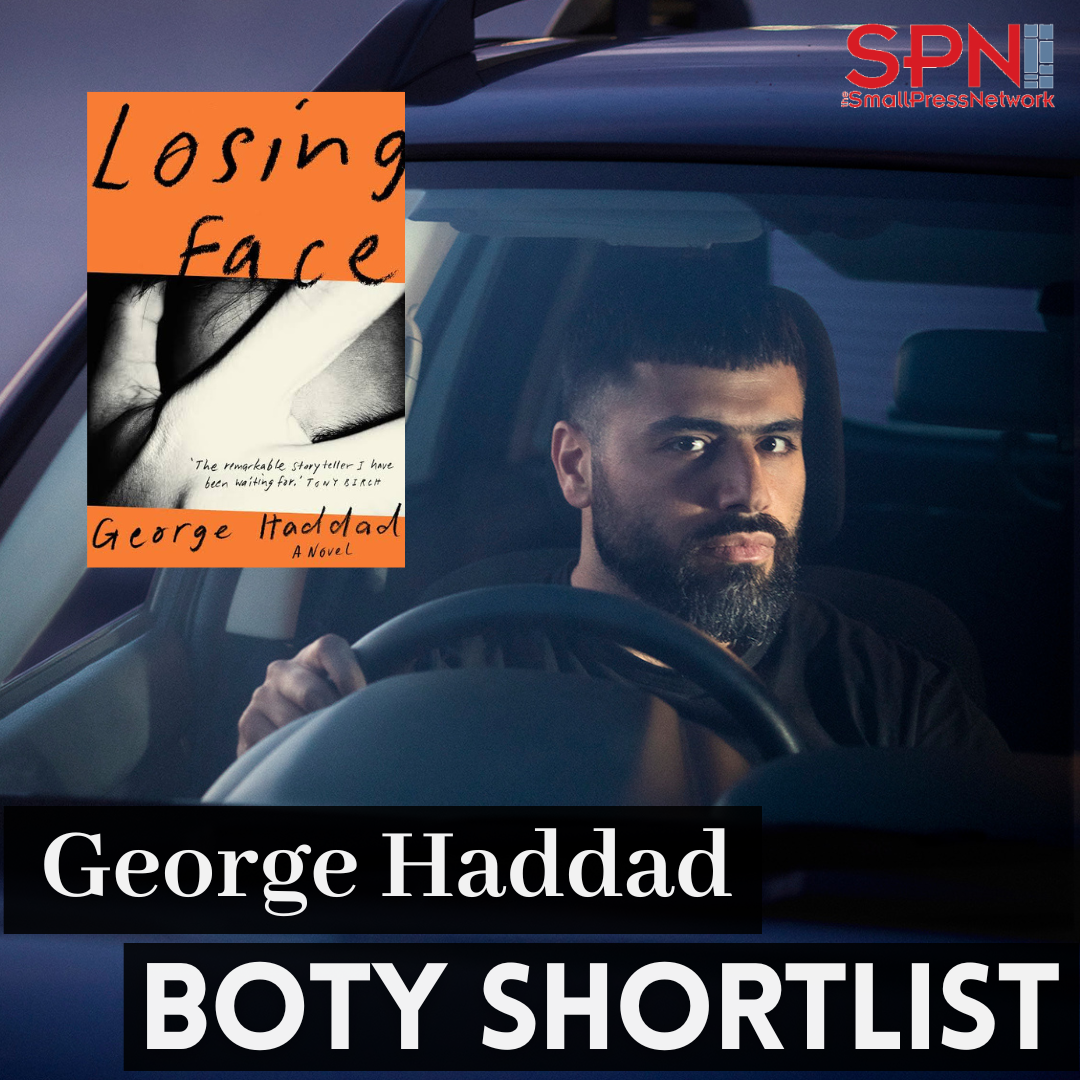

In conversation with BOTY shortlisted author George Haddad

For a novel about violence, Losing Face is surprisingly tender. George Haddad is a writer with a talent for voice and place, vividly capturing the intensity of Western Sydney. Haddad uses layered intergenerational storytelling to demonstrate the complexity with which lives intertwine and unravel around a violent crime. He avoids delivering neat and easy answers but instead lingers in places that we usually want to look away from. But we don’t look away; Haddad has achieved a page-turning urgency that makes this a compelling reading experience.

—BOTY 2023 judging panel

We were lucky enough to chat with George about Losing Face, one of the shortlisted titles for the 2023 SPN Book of the Year Award. The award ceremony will take place on 24 November and the winner will be announced on the night.

To see the full shortlist, click here.

To book a ticket to the BOTY award ceremony, click here. All the shortlisted books will be available for purchase at the Independent Publishing Conference through our conference bookseller, Readings. They can also be ordered through the Readings website.

Q. First off, congratulations on the recent achievements of Losing Face, which merited you as one of SMH’s Best Young Australian Novelists, as well as the title appearing on the Miles Franklin Literary Award longlist and the shortlist for both the New Australian Fiction Prize and the Prime Minister’s Literary Awards. In a previous interview, you mentioned that Losing Face was something that your body had to write. Was the writing process for Losing Face a kind of meditation for you by way of your drive to write it, or did you experience moments where ‘perspiration’ played a heavy hand? If so, how did you overcome the more difficult periods of writing Losing Face?

For me, writing is always an act of meditation and catharsis. Writing through the body and through its memory, trauma, experience, desire, is unavoidable. That’s not to suggest that writing is as fluid as breathing and thinking. There are certainly moments when the process, like the body, is blocked, tired, dysfunctional, and that is when I just listen and relax and don’t write at all.

Q. Losing Face is an intergenerational novel told from the lens of two very different (but not altogether unalike) characters. Could you offer any insight into the writing process for Losing Face, from the first draft and how long it took to write, to the practice of self-editing and scene amendments? Were there any major changes from the first draft to the final published title?

Losing Face started out purely through Joey’s perspective, but around 10,000 words in I realised that the novel needed another viewpoint. I was already very fond of Elaine, Joey’s grandmother, and so it had to be hers. The process of writing through Elaine was seriously organic. I knew her well and I found it was super important to do a character like hers justice because we don’t often come across them in Australian literature. I was working on the novel for around three years from inception to publishable copy and this was mainly because the novel was part of my doctoral studies that addressed the intersection of shame, masculinities and suburbia in contemporary Australian fiction. I’m a big fan of editing my own work. I find it exciting to finesse sentences, words, scenes, so that they are as potent as they can be.

Q. There’s a passage early on in Losing Face which briefly explores cognitive science and the phenomena of our biases in perception which ultimately convince us into a collective illusion. It’s clear that society experiences the effects of illusions through forms of maladaptive behaviour – based on, for the most part, shame. Shame is a principal theme in Losing Face, and the sense of it underlies most of the characters’ performances as they function throughout their day-to-day lives. The effects of this experiencing of shame ranges from the destructive and harmful (Boxer/Haz), the fearful (Elaine), and the avoidant (Joey). If violent acts do not occur in a bubble of their own volition, how do you think shame can be faced and reduced in oneself and others so events of violence can be drastically decreased?

Shame is actually a really important aspect of our emotional make-up. I’m all for harnessing and using shame productively to curb certain behaviours and to learn how best we can live considerately with people in our communities. In saying that I do think our relationship to shame, and perhaps even our definition of it and our approach towards it, has gone somewhat awry in modern times. Shame needn’t always be synonymous with punishment. It doesn’t always have to stifle us when we feel it. The most important thing to remember is that like joy, it is necessary to feel if we are to exist in societies, and that it can be the ignition for education, growth, care, improvement. The characters in Losing Face, like so many of us, haven’t been given the tools or the language to process their shame in constructive and conducive ways. This is mostly because colonial society has taught us to diminish the feeling which ends up creating a classic pressure-cooker situation.

George Haddad is an award-winning writer, artist and academic practising on Gadigal land. His novella, Populate and Perish, was the winner of the 2016 Viva La Novella competition and his short story Kátharsis was awarded the 2018 Neilma Sidney Prize. George’s novel, Losing Face, was longlisted for the Miles Franklin Award and shortlisted for The Readings Prize. In 2023 he was named a Sydney Morning Herald Best Young Novelist. He is a lecturer and researcher at the Writing and Society Research Centre, Western Sydney University. George’s text, sound, performance and installation based art has been exhibited at Firstdraft, Casula Powerhouse Arts Centre, ReadingRoom and Metro Arts.