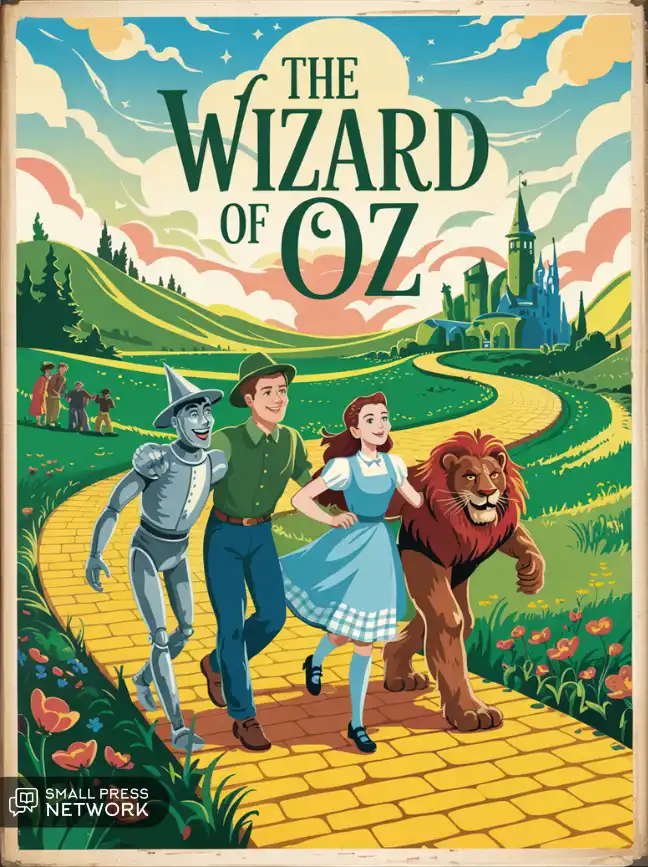

Chapter IV

The Road Through the Forest

After a few hours the road began to be rough, and the walking grew so

difficult that the Scarecrow often stumbled over the yellow bricks, which

were here very uneven. Sometimes, indeed, they were broken or missing

altogether, leaving holes that Toto jumped across and Dorothy walked

around. As for the Scarecrow, having no brains, he walked straight ahead,

and so stepped into the holes and fell at full length on the hard bricks. It

never hurt him, however, and Dorothy would pick him up and set him upon

his feet again, while he joined her in laughing merrily at his own mishap.

The farms were not nearly so well cared for here as they were farther

back. There were fewer houses and fewer fruit trees, and the farther they

went the more dismal and lonesome the country became.

At noon they sat down by the roadside, near a little brook, and Dorothy

opened her basket and got out some bread. She offered a piece to the

Scarecrow, but he refused.

“I am never hungry,” he said, “and it is a lucky thing I am not, for my mouth

is only painted, and if I should cut a hole in it so I could eat, the straw I am

stuffed with would come out, and that would spoil the shape of my head.”

Dorothy saw at once that this was true, so she only nodded and went on

eating her bread.

“Tell me something about yourself and the country you came from,” said

the Scarecrow, when she had finished her dinner. So she told him all about

Kansas, and how gray everything was there, and how the cyclone had carried

her to this queer Land of Oz.

The Scarecrow listened carefully, and said, “I cannot understand why you

should wish to leave this beautiful country and go back to the dry, gray place

you call Kansas.”

“That is because you have no brains” answered the girl. “No matter how

dreary and gray our homes are, we people of flesh and blood would rather

live there than in any other country, be it ever so beautiful. There is no place

like home.”

The Scarecrow sighed.

“Of course I cannot understand it,” he said. “If your heads were stuffed

with straw, like mine, you would probably all live in the beautiful places,

and then Kansas would have no people at all. It is fortunate for Kansas that

you have brains.”

“Won’t you tell me a story, while we are resting?” asked the child.

The Scarecrow looked at her reproachfully, and answered:

“My life has been so short that I really know nothing whatever. I was only

made day before yesterday. What happened in the world before that time is

all unknown to me. Luckily, when the farmer made my head, one of the first

things he did was to paint my ears, so that I heard what was going on. There

was another Munchkin with him, and the first thing I heard was the farmer

saying, ‘How do you like those ears?’

“‘They aren’t straight,’” answered the other.

“‘Never mind,’” said the farmer. “‘They are ears just the same,’” which

was true enough.

“‘Now I’ll make the eyes,’” said the farmer. So he painted my right eye,

and as soon as it was finished I found myself looking at him and at everything

around me with a great deal of curiosity, for this was my first glimpse of the

world.

“‘That’s a rather pretty eye,’” remarked the Munchkin who was watching

the farmer. “‘Blue paint is just the color for eyes.’

“‘I think I’ll make the other a little bigger,’” said the farmer. And when the

second eye was done I could see much better than before. Then he made my

nose and my mouth. But I did not speak, because at that time I didn’t know

what a mouth was for. I had the fun of watching them make my body and my

arms and legs; and when they fastened on my head, at last, I felt very proud,

for I thought I was just as good a man as anyone.

“‘This fellow will scare the crows fast enough,’ said the farmer. ‘He looks

just like a man.’

“‘Why, he is a man,’ said the other, and I quite agreed with him. The

farmer carried me under his arm to the cornfield, and set me up on a tall

stick, where you found me. He and his friend soon after walked away and left

me alone.

“I did not like to be deserted this way. So I tried to walk after them. But

my feet would not touch the ground, and I was forced to stay on that pole. It

was a lonely life to lead, for I had nothing to think of, having been made such

a little while before. Many crows and other birds flew into the cornfield, but

as soon as they saw me they flew away again, thinking I was a Munchkin; and

this pleased me and made me feel that I was quite an important person. By

and by an old crow flew near me, and after looking at me carefully he

perched upon my shoulder and said:

“‘I wonder if that farmer thought to fool me in this clumsy manner. Any

crow of sense could see that you are only stuffed with straw.’ Then he

hopped down at my feet and ate all the corn he wanted. The other birds,

seeing he was not harmed by me, came to eat the corn too, so in a short time

there was a great flock of them about me.

“I felt sad at this, for it showed I was not such a good Scarecrow after all;

but the old crow comforted me, saying, ‘If you only had brains in your head

you would be as good a man as any of them, and a better man than some of

them. Brains are the only things worth having in this world, no matter

whether one is a crow or a man.’

“After the crows had gone I thought this over, and decided I would try hard

to get some brains. By good luck you came along and pulled me off the stake,

and from what you say I am sure the Great Oz will give me brains as soon as

we get to the Emerald City.”

“I hope so,” said Dorothy earnestly, “since you seem anxious to have

them.”

“Oh, yes; I am anxious,” returned the Scarecrow. “It is such an

uncomfortable feeling to know one is a fool.”

“Well,” said the girl, “let us go.” And she handed the basket to the

Scarecrow.

There were no fences at all by the roadside now, and the land was rough

and untilled. Toward evening they came to a great forest, where the trees

grew so big and close together that their branches met over the road of

yellow brick. It was almost dark under the trees, for the branches shut out the

daylight; but the travelers did not stop, and went on into the forest.

“If this road goes in, it must come out,” said the Scarecrow, “and as the

Emerald City is at the other end of the road, we must go wherever it leads

us.”

“Anyone would know that,” said Dorothy.

“Certainly; that is why I know it,” returned the Scarecrow. “If it required

brains to figure it out, I never should have said it.”

After an hour or so the light faded away, and they found themselves

stumbling along in the darkness. Dorothy could not see at all, but Toto could,

for some dogs see very well in the dark; and the Scarecrow declared he

could see as well as by day. So she took hold of his arm and managed to get

along fairly well.

“If you see any house, or any place where we can pass the night,” she said,

“you must tell me; for it is very uncomfortable walking in the dark.”

Soon after the Scarecrow stopped.

“I see a little cottage at the right of us,” he said, “built of logs and

branches. Shall we go there?”

“Yes, indeed,” answered the child. “I am all tired out.”

So the Scarecrow led her through the trees until they reached the cottage,

and Dorothy entered and found a bed of dried leaves in one corner. She lay

down at once, and with Toto beside her soon fell into a sound sleep. The

Scarecrow, who was never tired, stood up in another corner and waited

patiently until morning came.