Chapter Six

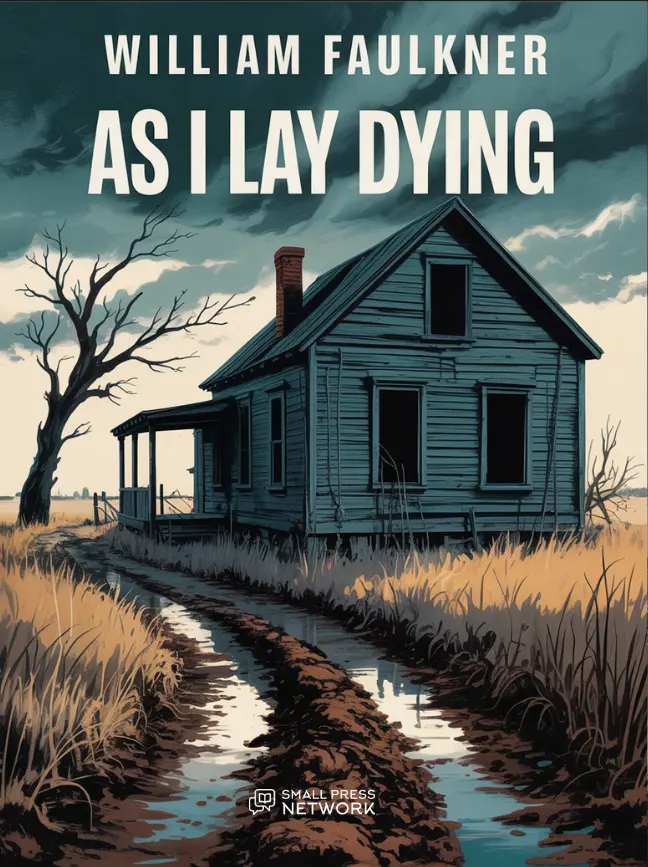

The Reverend Casy and young Tom stood on the hill and looked down on the Joad place. The small unpainted house was mashed at one corner, and it had been pushed off its foundations so that it slumped at an angle, its blind front windows pointing at a spot of sky well above the horizon. The fences were gone and the cotton grew in the dooryard and up against the house, and the cotton was about the shed barn. The outhouse lay on its side, and the cotton grew close against it. Where the dooryard had been pounded hard by the bare feet of children and by stamping horses’ hooves and by the broad wagon wheels, it was cultivated now, and the dark green, dusty cotton grew. Young Tom stared for a long time at the ragged willow beside the dry horse trough, at the concrete base where the pump had been. “Jesus!” he said at last. “Hell musta popped here. There ain’t nobody livin’ there.” At last he moved quickly down the hill, and Casy followed him. He looked into the barn shed, deserted, a little ground straw on the floor, and at the mule stall in the corner. And as he looked in, there was a skittering on the floor and a family of mice faded in under the straw. Joad paused at the entrance to the tool-shed leanto, and no tools were there—a broken plow point, a mess of hay wire in the corner, an iron wheel from a hayrake and a rat-gnawed mule collar, a flat gallon oil can crusted with dirt and oil, and a pair of torn overalls hanging on a nail. “There ain’t nothin’ left,” said Joad. “We had pretty nice tools. There ain’t nothin’ left.”

Casy said, “If I was still a preacher I’d say the arm of the Lord had struck. But now I don’t know what happened. I been away. I didn’t hear nothin’.” They walked toward the concrete well-cap, walked through cotton plants to get to it, and the bolls were forming on the cotton, and the land was cultivated.

“We never planted here,” Joad said. “We always kept this clear. Why, you can’t get a horse in now without he tromps the cotton.” They paused at the dry watering trough, and the proper weeds that should grow under a trough were gone and the old thick wood of the trough was dry and cracked. On the well-cap the bolts that had held the pump stuck up, their threads rusty and the nuts gone. Joad looked into the tube of the well and spat and listened. He dropped a clod down the well and listened. “She was a good well,” he said. “I can’t hear water.” He seemed reluctant to go to the house. He dropped clod after clod down the well. “Maybe they’re all dead,” he said. “But somebody’d a told me. I’d a got word some way.”

“Maybe they left a letter or something to tell in the house. Would they of knowed you was comin’ out?”

“I don’ know,” said Joad. “No, I guess not. I didn’ know myself till a week ago.”

“Le’s look in the house. She’s all pushed out a shape. Something knocked the hell out of her.” They walked slowly toward the sagging house. Two of the supports of the porch roof were pushed out so that the roof flopped down on one end. And the house-corner

was crushed in. Through a maze of splintered wood the room at the corner was visible.

The front door hung open inward, and a low strong gate across the front door hung outward on leather hinges.

Joad stopped at the step, a twelve-by-twelve timber. “Doorstep’s here,” he said. “But they’re gone—or Ma’s dead.” He pointed to the low gate across the front door. “If Ma was anywheres about, that gate’d be shut an’ hooked. That’s one thing she always done —seen that gate was shut.” His eyes were warm. “Ever since the pig got in over to Jacobs’ an’ et the baby. Milly Jacobs was jus’ out in the barn. She come in while the pig was still eatin’ it. Well, Milly Jacobs was in a family way, an’ she went ravin’. Never did get over it. Touched ever since. But Ma took a lesson from it. She never lef’ that pig gate open ’less she was in the house herself. Never did forget. No—they’re gone—or dead.”

He climbed to the split porch and looked into the kitchen. The windows were broken out, and throwing rocks lay on the floor, and the floor and walls sagged steeply away from the door, and the sifted dust was on the boards. Joad pointed to the broken glass and the rocks. “Kids,” he said. “They’ll go twenty miles to bust a window. I done it myself. They know when a house is empty, they know. That’s the fust thing kids do when folks move out.” The kitchen was empty of furniture, stove gone and the round stovepipe hole in the wall showing light. On the sink shelf lay an old beer opener and a broken fork with its wooden handle gone. Joad slipped cautiously into the room, and the floor groaned under his weight. An old copy of the Philadelphia Ledger was on the floor against the wall, its pages yellow and curling. Joad looked into the bedroom—no bed, no chairs, nothing. On the wall a picture of an Indian girl in color, labeled Red Wing. A bed slat leaning against the wall, and in one corner a woman’s high button shoe, curled up at the toe and broken over the instep. Joad picked it up and looked at it. “I remember this,” he said. “This was Ma’s. It’s all wore out now. Ma liked them shoes. Had ’em for years. No, they’ve went— an’ took ever’thing.”

The sun had lowered until it came through the angled end windows now, and it flashed on the edges of the broken glass. Joad turned at last and went out and crossed the porch. He sat down on the edge of it and rested his bare feet on the twelve-by-twelve step. The evening light was on the fields, and the cotton plants threw long shadows on the ground, and the molting willow tree threw a long shadow.

Casy sat down beside Joad. “They never wrote you nothin’?” he asked.

“No. Like I said, they wasn’t people to write. Pa could write, but he wouldn’. Didn’t like to. It give him the shivers to write. He could work out a catalogue order as good as the nex’ fella, but he wouldn’ write no letters just for ducks.” They sat side by side, staring off into the distance. Joad laid his rolled coat on the porch beside him. His independent hands rolled a cigarette, smoothed it and lighted it, and he inhaled deeply and blew the smoke out through his nose. “Somepin’s wrong,” he said. “I can’t put my finger on her. I got an itch that somepin’s wronger’n hell. Just this house pushed aroun’ an’ my folks gone.”

Casy said, “Right over there the ditch was, where I done the baptizin’. You wasn’t mean, but you was tough. Hung onto that little girl’s pigtail like a bulldog. We baptize’ you both in the name of the Holy Ghos’, and still you hung on. Ol’ Tom says, ‘Hol’ ’im under water.’ So I shove your head down till you start to bubblin’ before you’d let go a

that pigtail. You wasn’t mean, but you was tough. Sometimes a tough kid grows up with a big jolt of the sperit in him.”

A lean gray cat came sneaking out of the barn and crept through the cotton plants to the end of the porch. It leaped silently up to the porch and crept low-belly toward the men. It came to a place between and behind the two, and then it sat down, and its tail stretched out straight and flat to the floor, and the last inch of it flicked. The cat sat and looked off into the distance where the men were looking.

Joad glanced around at it. “By God! Look who’s here. Somebody stayed.” He put out his hand, but the cat leaped away out of reach and sat down and licked the pads of its lifted paw. Joad looked at it, and his face was puzzled. “I know what’s the matter,” he cried. “That cat jus’ made me figger what’s wrong.”

“Seems to me there’s lots wrong,” said Casy.

“No, it’s more’n jus’ this place. Whyn’t that cat jus’ move in with some neighbors— with the Rances. How come nobody ripped some lumber off this house? Ain’t been nobody here for three-four months, an’ nobody’s stole no lumber. Nice planks on the barn shed, plenty good planks on the house, winda frames—an’ nobody’s took ’em. That ain’t right. That’s what was botherin’ me, an’ I couldn’t catch hold of her.”

“Well, what’s that figger out for you?” Casy reached down and slipped off his sneakers and wriggled his long toes on the step.

“I don’ know. Seems like maybe there ain’t any neighbors. If there was, would all them nice planks be here? Why, Jesus Christ! Albert Rance took his family, kids an’ dogs an’ all, into Oklahoma City one Christmus. They was gonna visit with Albert’s cousin.

Well, folks aroun’ here thought Albert moved away without sayin’ nothin’—figgered maybe he got debts or some woman’s squarin’ off at him. When Albert come back a week later there wasn’t a thing lef’ in his house—stove was gone, beds was gone, winda frames was gone, an’ eight feet of plankin’ was gone off the south side of the house so you could look right through her. He come drivin’ home just as Muley Graves was goin’ away with the doors an’ the well pump. Took Albert two weeks drivin’ aroun’ the neighbors’ ’fore he got his stuff back.”

Casy scratched his toes luxuriously. “Didn’t nobody give him an argument? All of ’em jus’ give the stuff up?”

“Sure. They wasn’t stealin’ it. They thought he lef’ it, an’ they jus’ took it. He got all of it back—all but a sofa pilla, velvet with a pitcher of an Injun on it. Albert claimed Grampa got it. Claimed Grampa got Injun blood, that’s why he wants that pitcher. Well, Grampa did get her, but he didn’t give a damn about the pitcher on it. He jus’ liked her.

Used to pack her aroun’ an’ he’d put her wherever he was gonna sit. He never would give her back to Albert. Says, ‘If Albert wants this pilla so bad, let him come an’ get her.

But he better come shootin’, ’cause I’ll blow his goddamn stinkin’ head off if he comes messin’ aroun’ my pilla.’ So finally Albert give up an’ made Grampa a present of that pilla. It give Grampa idears, though. He took to savin’ chicken feathers. Says he’s gonna have a whole damn bed of feathers. But he never got no feather bed. One time Pa got mad at a skunk under the house. Pa slapped that skunk with a two-by-four, and Ma burned all Grampa’s feathers so we could live in the house.” He laughed. “Grampa’s a

tough ol’ bastard. Jus’ set on that Injun pilla an’ says, ‘Let Albert come an’ get her.

Why,’ he says, ‘I’ll take that squirt and wring ’im out like a pair of drawers.’ ”

The cat crept close between the men again, and its tail lay flat and its whiskers jerked now and then. The sun dropped low toward the horizon and the dusty air was red and golden. The cat reached out a gray questioning paw and touched Joad’s coat. He looked around. “Hell, I forgot the turtle. I ain’t gonna pack it all over hell.” He unwrapped the land turtle and pushed it under the house. But in a moment it was out, headed southwest as it had been from the first. The cat leaped at it and struck at its straining head and slashed at its moving feet. The old, hard, humorous head was pulled in, and the thick tail slapped in under the shell, and when the cat grew tired of waiting for it and walked off, the turtle headed on southwest again.

Young Tom Joad and the preacher watched the turtle go—waving its legs and boosting its heavy, high-domed shell along toward the southwest. The cat crept along behind for a while, but in a dozen yards it arched its back to a strong taut bow and yawned, and came stealthily back toward the seated men.

“Where the hell you s’pose he’s goin’?” said Joad. “I seen turtles all my life. They’re always goin’ someplace. They always seem to want to get there.” The gray cat seated itself between and behind them again. It blinked slowly. The skin over its shoulders jerked forward under a flea, and then slipped slowly back. The cat lifted a paw and inspected it, flicked its claws out and in again experimentally, and licked its pads with a shell-pink tongue. The red sun touched the horizon and spread out like a jellyfish, and the sky above it seemed much brighter and more alive than it had been. Joad unrolled his new yellow shoes from his coat, and he brushed his dusty feet with his hand before he slipped them on.

The preacher, staring off across the fields, said, “Somebody’s comin’. Look! Down there, right through the cotton.”

Joad looked where Casy’s finger pointed. “Comin’ afoot,” he said. “Can’t see ’im for the dust he raises. Who the hell’s comin’ here?” They watched the figure approaching in the evening light, and the dust it raised was reddened by the setting sun. “Man,” said Joad. The man drew closer, and as he walked past the barn, Joad said, “Why, I know him.

You know him—that’s Muley Graves.” And he called, “Hey, Muley! How ya?”

The approaching man stopped, startled by the call, and then he came on quickly. He was a lean man, rather short. His movements were jerky and quick. He carried a gunny sack in his hand. His blue jeans were pale at knee and seat, and he wore an old black suit coat, stained and spotted, the sleeves torn loose from the shoulders in back, and ragged holes worn through at the elbows. His black hat was as stained as his coat, and the band, torn half free, flopped up and down as he walked. Muley’s face was smooth and unwrinkled, but it wore the truculent look of a bad child’s, the mouth held tight and small, the little eyes half scowling, half petulant.

“You remember Muley,” Joad said softly to the preacher.

“Who’s that?” the advancing man called. Joad did not answer. Muley came close, very close, before he made out the faces. “Well, I’ll be damned,” he said. “It’s Tommy Joad. When’d you get out, Tommy?”

“Two days ago,” said Joad. “Took a little time to hitch-hike home. An’ look here what I find. Where’s my folks, Muley? What’s the house all smashed up for, an’ cotton planted in the dooryard?”

“By God, it’s lucky I come by!” said Muley. “ ’Cause ol’ Tom worried himself. When they was fixin’ to move I was settin’ in the kitchen there. I jus’ tol’ Tom I wan’t gonna move, by God. I tol’ him that, an’ Tom says, ‘I’m worryin’ myself about Tommy. S’pose he comes home an’ they ain’t nobody here. What’ll he think?’ I says, ‘Whyn’t you write down a letter?’ An’ Tom says, ‘Maybe I will. I’ll think about her. But if I don’t, you keep your eye out for Tommy if you’re still aroun’.’ ‘I’ll be aroun’,’ I says. ‘I’ll be aroun’ till hell freezes over. There ain’t nobody can run a guy name of Graves outa this country.’ An’ they ain’t done it, neither.”

Joad said impatiently, “Where’s my folks? Tell about you standin’ up to ’em later, but where’s my folks?”

“Well, they was gonna stick her out when the bank come to tractorin’ off the place.

Your grampa stood out here with a rifle, an’ he blowed the headlights off that cat’, but she come on just the same. Your grampa didn’t wanta kill the guy drivin’ that cat’, an’ that was Willy Feeley, an’ Willy knowed it, so he jus’ come on, an’ bumped the hell outa the house, an’ give her a shake like a dog shakes a rat. Well, it took somepin outa Tom.

Kinda got into ’im. He ain’t been the same ever since.”

“Where is my folks?” Joad spoke angrily.

“What I’m tellin’ you. Took three trips with your Uncle John’s wagon. Took the stove an’ the pump an’ the beds. You should a seen them beds go out with all them kids an’ your granma an’ grampa settin’ up against the headboard, an’ your brother Noah settin’ there smokin’ a cigareet, an’ spittin’ la-de-da over the side of the wagon.” Joad opened his mouth to speak. “They’re all at your Uncle John’s,” Muley said quickly.

“Oh! All at John’s. Well, what they doin’ there? Now stick to her for a second, Muley. Jus’ stick to her. In jus’ a minute you can go on your own way. What they doin’ there?”

“Well, they been choppin’ cotton, all of ’em, even the kids an’ your grampa. Gettin’ money together so they can shove on west. Gonna buy a car and shove on west where it’s easy livin’. There ain’t nothin’ here. Fifty cents a clean acre for choppin’ cotton, an’

folks beggin’ for the chance to chop.”

“An’ they ain’t gone yet?”

“No,” said Muley. “Not that I know. Las’ I heard was four days ago when I seen your brother Noah out shootin’ jackrabbits, an’ he says they’re aimin’ to go in about two weeks. John got his notice he got to get off. You jus’ go on about eight miles to John’s place. You’ll find your folks piled in John’s house like gophers in a winter burrow.”

“O.K.” said Joad. “Now you can ride on your own way. You ain’t changed a bit, Muley. If you want to tell about somepin off northwest, you point your nose straight southeast.”

Muley said truculently, “You ain’t changed neither. You was a smart-aleck kid, an’ you’re still a smart aleck. You ain’t tellin’ me how to skin my life, by any chancet?”

Joad grinned. “No, I ain’t. If you wanta drive your head into a pile a broken glass, there ain’t nobody can tell you different. You know this here preacher, don’t you, Muley?

Rev. Casy.”

“Why, sure, sure. Didn’t look over. Remember him well.” Casy stood up and the two shook hands. “Glad to see you again,” said Muley. “You ain’t been aroun’ for a hell of a long time.”

“I been off a-askin’ questions,” said Casy. “What happened here? Why they kickin’ folks off the lan’?”

Muley’s mouth snapped shut so tightly that a little parrot’s beak in the middle of his upper lip stuck down over his under lip. He scowled. “Them sons-a-bitches,” he said.

“Them dirty sons-a-bitches. I tell ya, men, I’m stayin’. They ain’t gettin’ rid a me. If they throw me off, I’ll come back, an’ if they figger I’ll be quiet underground, why, I’ll take couple-three of the sons-a-bitches along for company.” He patted a heavy weight in his side coat pocket. “I ain’t a-goin’. My pa come here fifty years ago. An’ I ain’t a-goin’.”

Joad said, “What’s the idear of kickin’ the folks off?”

“Oh! They talked pretty about it. You know what kinda years we been havin’. Dust comin’ up an’ spoilin’ ever’thing so a man didn’t get enough crop to plug up an ant’s ass.

An’ ever’body got bills at the grocery. You know how it is. Well, the folks that owns the lan’ says, ‘We can’t afford to keep no tenants.’ An’ they says, ‘The share a tenant gets is jus’ the margin a profit we can’t afford to lose.’ An’ they says, ‘If we put all our lan’ in one piece we can jus’ hardly make her pay.’ So they tractored all the tenants off a the lan’. All ’cept me, an’ by God I ain’t goin’. Tommy, you know me. You knowed me all

your life.”

“Damn right,” said Joad, “all my life.”

“Well, you know I ain’t a fool. I know this land ain’t much good. Never was much good ’cept for grazin’. Never should a broke her up. An’ now she’s cottoned damn near to death. If on’y they didn’ tell me I got to get off, why, I’d prob’y be in California right now a-eatin’ grapes an’ a-pickin’ an orange when I wanted. But them sons-a-bitches says I got to get off—an’, Jesus Christ, a man can’t, when he’s tol’ to!”

“Sure,” said Joad. “I wonder Pa went so easy. I wonder Grampa didn’ kill nobody.

Nobody never tol’ Grampa where to put his feet. An’ Ma ain’t nobody you can push aroun’, neither. I seen her beat the hell out of a tin peddler with a live chicken one time ’cause he give her a argument. She had the chicken in one han’, an’ the ax in the other, about to cut its head off. She aimed to go for that peddler with the ax, but she forgot which hand was which, an’ she takes after him with the chicken. Couldn’ even eat that chicken when she got done. They wasn’t nothing but a pair a legs in her han’. Grampa throwed his hip outa joint laughin’. How’d my folks go so easy?”

“Well, the guy that come aroun’ talked nice as pie. ‘You got to get off. It ain’t my fault.’ ‘Well,’ I says, ‘whose fault is it? I’ll go an’ I’ll nut the fella.’ ‘It’s the Shawnee Lan’ an’ Cattle Company. I jus’ got orders.’ ‘Who’s the Shawnee Lan’ an’ Cattle Company?’ ‘It ain’t nobody. It’s a company.’ Got a fella crazy. There wasn’t nobody you could lay for. Lot a the folks jus’ got tired out lookin’ for somepin to be mad at—but not me. I’m mad at all of it. I’m stayin’.”

A large red drop of sun lingered on the horizon and then dripped over and was gone, and the sky was brilliant over the spot where it had gone, and a torn cloud, like a bloody rag, hung over the spot of its going. And dusk crept over the sky from the eastern horizon, and darkness crept over the land from the east. The evening star flashed and glittered in the dusk. The gray cat sneaked away toward the open barn shed and passed inside like a shadow.

Joad said, “Well, we ain’t gonna walk no eight miles to Uncle John’s place tonight.

My dogs is burned up. How’s it if we go to your place, Muley? That’s on’y about a mile.”

“Won’t do no good.” Muley seemed embarrassed. “My wife an’ the kids an’ her brother all took an’ went to California. They wasn’t nothin’ to eat. They wasn’t as mad as me, so they went. They wasn’t nothin’ to eat here.”

The preacher stirred nervously. “You should of went too. You shouldn’t of broke up the fambly.”

“I couldn’,” said Muley Graves. “Somepin jus’ wouldn’ let me.”

“Well, by God, I’m hungry,” said Joad. “Four solemn years I been eatin’ right on the minute. My guts is yellin’ bloody murder. What you gonna eat, Muley? How you been gettin’ your dinner?”

Muley said ashamedly, “For a while I et frogs an’ squirrels an’ prairie dogs sometimes. Had to do it. But now I got some wire nooses on the tracks in the dry stream brush. Get rabbits, an’ sometimes a prairie chicken. Skunks get caught, an’ coons, too.”

He reached down, picked up his sack, and emptied it on the porch. Two cottontails and a jackrabbit fell out and rolled over limply, soft and furry.

“God Awmighty,” said Joad, “it’s more’n four years sence I’ve et fresh-killed meat.”

Casy picked up one of the cottontails and held it in his hand. “You sharin’ with us, Muley Graves?” he asked.

Muley fidgeted in embarrassment. “I ain’t got no choice in the matter.” He stopped on the ungracious sound of his words. “That ain’t like I mean it. That ain’t. I mean”—he stumbled—“what I mean, if a fella’s got somepin to eat an’ another fella’s hungry—why, the first fella ain’t got no choice. I mean, s’pose I pick up my rabbits an’ go off somewheres an’ eat ’em. See?”

“I see,” said Casy. “I can see that. Muley sees somepin there, Tom. Muley’s got a-holt of somepin, an’ it’s too big for him, an’ it’s too big for me.”

Young Tom rubbed his hands together. “Who got a knife? Le’s get at these here miserable rodents. Le’s get at ’em.”

Muley reached in his pants pocket and produced a large horn-handled pocket knife.

Tom Joad took it from him, opened a blade, and smelled it. He drove the blade again and again into the ground and smelled it again, wiped it on his trouser leg, and felt the edge with his thumb.

Muley took a quart bottle of water out of his hip pocket and set it on the porch. “Go easy on that there water,” he said. “That’s all there is. This here well’s filled in.”

Tom took up a rabbit in his hand. “One of you go get some bale wire outa the barn.

We’ll make a fire with some a this broken plank from the house.” He looked at the dead rabbit. “There ain’t nothin’ so easy to get ready as a rabbit,” he said. He lifted the skin of the back, slit it, put his fingers in the hole, and tore the skin off. It slipped off like a stocking, slipped off the body to the neck, and off the legs to the paws. Joad picked up the knife again and cut off head and feet. He laid the skin down, slit the rabbit along the ribs, shook out the intestines onto the skin, and then threw the mess off into the cotton field. And the clean-muscled little body was ready. Joad cut off the legs and cut the meaty back into two pieces. He was picking up the second rabbit when Casy came back with a snarl of bale wire in his hand. “Now build up a fire and put some stakes up,” said Joad. “Jesus Christ, I’m hungry for these here creatures!” He cleaned and cut up the rest of the rabbits and strung them on the wire. Muley and Casy tore splintered boards from the wrecked house-corner and started a fire, and they drove a stake into the ground on each side to hold the wire.

Muley came back to Joad. “Look out for boils on that jackrabbit,” he said. “I don’t like to eat no jackrabbit with boils.” He took a little cloth bag from his pocket and put it on the porch.

Joad said, “The jack was clean as a whistle—Jesus God, you got salt too? By any chance you got some plates an’ a tent in your pocket?” He poured salt in his hand and sprinkled it over the pieces of rabbit strung on the wire.

The fire leaped and threw shadows on the house, and the dry wood crackled and snapped. The sky was almost dark now and the stars were out sharply. The gray cat came out of the barn shed and trotted miaowing toward the fire, but, nearly there, it turned and went directly to one of the little piles of rabbit entrails on the ground. It chewed and swallowed, and the entrails hung from its mouth.

Casy sat on the ground beside the fire, feeding it broken pieces of board, pushing the long boards in as the flame ate off their ends. The evening bats flashed into the firelight and out again. The cat crouched back and licked its lips and washed its face and whiskers.

Joad held up his rabbit-laden wire between his two hands and walked to the fire.

“Here, take one end, Muley. Wrap your end around that stake. That’s good, now! Let’s tighten her up. We ought to wait till the fire’s burned down, but I can’t wait.” He made the wire taut, then found a stick and slipped the pieces of meat along the wire until they were over the fire. And the flames licked up around the meat and hardened and glazed the surfaces. Joad sat down by the fire, but with his stick he moved and turned the rabbit so that it would not become sealed to the wire. “This here is a party,” he said. “Salt, Muley’s got, an’ water an’ rabbits. I wish he got a pot of hominy in his pocket. That’s all I wish.”

Muley said over the fire, “You fellas’d think I’m touched, the way I live.”

“Touched, nothin’,” said Joad. “If you’re touched, I wisht ever’body was touched.”

Muley continued, “Well, sir, it’s a funny thing. Somepin went an’ happened to me when they tol’ me I had to get off the place. Fust I was gonna go in an’ kill a whole flock a people. Then all my folks all went away out west. An’ I got wanderin’ aroun’. Jus’ walkin’ aroun’. Never went far. Slep’ where I was. I was gonna sleep here tonight. That’s

why I come. I’d tell myself, ‘I’m lookin’ after things so when all the folks come back it’ll be all right.’ But I knowed that wan’t true. There ain’t nothin’ to look after. The folks ain’t never comin’ back. I’m jus’ wanderin’ aroun’ like a damn ol’ graveyard ghos’.”

“Fella gets use’ to a place, it’s hard to go,” said Casy. “Fella gets use’ to a way a thinkin’, it’s hard to leave. I ain’t a preacher no more, but all the time I find I’m prayin’, not even thinkin’ what I’m doin’.”

Joad turned the pieces of meat over on the wire. The juice was dripping now, and every drop, as it fell in the fire, shot up a spurt of flame. The smooth surface of the meat was crinkling up and turning a faint brown. “Smell her,” said Joad. “Jesus, look down an’ jus’ smell her!”

Muley went on, “Like a damn ol’ graveyard ghos’. I been goin’ aroun’ the places where stuff happened. Like there’s a place over by our forty; in a gully they’s a bush.

Fust time I ever laid with a girl was there. Me fourteen an’ stampin’ an’ jerkin’ an’ snortin’ like a buck deer, randy as a billygoat. So I went there an’ I laid down on the groun’, an’ I seen it all happen again. An’ there’s the place down by the barn where Pa got gored to death by a bull. An’ his blood is right in that groun’, right now. Mus’ be.

Nobody never washed it out. An’ I put my han’ on that groun’ where my own pa’s blood is part of it.” He paused uneasily. “You fellas think I’m touched?”

Joad turned the meat, and his eyes were inward. Casy, feet drawn up, stared into the fire. Fifteen feet back from the men the fed cat was sitting, the long gray tail wrapped neatly around the front feet. A big owl shrieked as it went overhead, and the firelight showed its white underside and the spread of its wings.

“No,” said Casy. “You’re lonely—but you ain’t touched.”

Muley’s tight little face was rigid. “I put my han’ right on the groun’ where that blood is still. An’ I seen my pa with a hole through his ches’, an’ I felt him shiver up against me like he done, an’ I seen him kind of settle back an’ reach with his han’s an’ his feet. An’ I seen his eyes all milky with hurt, an’ then he was still an’ his eyes so clear —lookin’ up. An’ me a little kid settin’ there, not cryin’ nor nothin’, jus’ settin’ there.”

He shook his head sharply. Joad turned the meat over and over. “An’ I went in the room where Joe was born. Bed wasn’t there, but it was the room. An’ all them things is true, an’ they’re right in the place they happened. Joe come to life right there. He give a big ol’ gasp an’ then he let out a squawk you could hear a mile, an’ his granma standin’ there says, ‘That’s a daisy, that’s a daisy,’ over an’ over. An’ her so proud she bust three cups that night.”

Joad cleared his throat. “Think we better eat her now.”

“Let her get good an’ done, good an’ brown, awmost black,” said Muley irritably. “I wanta talk. I ain’t talked to nobody. If I’m touched, I’m touched, an’ that’s the end of it.

Like a ol’ graveyard ghos’ goin’ to neighbors’ houses in the night. Peters’, Jacobs’, Rance’s, Joad’s; an’ the houses all dark, standin’ like miser’ble ratty boxes, but they was good parties an’ dancin’. An’ there was meetin’s and shoutin’ glory. They was weddin’s, all in them houses. An’ then I’d want to go in town an’ kill folks. ’Cause what’d they take when they tractored the folks off the lan’? What’d they get so their ‘margin a profit’ was safe? They got Pa dyin’ on the groun’, an’ Joe yellin’ his first breath, an’ me jerkin’ like a billy goat under a bush in the night. What’d they get? God knows the lan’ ain’t no

good. Nobody been able to make a crop for years. But them sons-a-bitches at their desks, they jus’ chopped folks in two for their margin a profit. They jus’ cut ’em in two. Place where folks live is them folks. They ain’t whole, out lonely on the road in a piled-up car.

They ain’t alive no more. Them sons-a-bitches killed ’em.” And he was silent, his thin lips still moving, his chest still panting. He sat and looked down at his hands in the firelight. “I—I ain’t talked to nobody for a long time,” he apologized softly. “I been sneakin’ aroun’ like a ol’ graveyard ghos’.”

Casy pushed the long boards into the fire and the flames licked up around them and leaped up toward the meat again. The house cracked loudly as the cooler night air contracted the wood. Casy said quietly, “I gotta see them folks that’s gone out on the road. I got a feelin’ I got to see them. They gonna need help no preachin’ can give ’em.

Hope of heaven when their lives ain’t lived? Holy Sperit when their own sperit is downcast an’ sad? They gonna need help. They got to live before they can afford to die.”

Joad cried nervously, “Jesus Christ, le’s eat this meat ’fore it’s smaller’n a cooked mouse! Look at her. Smell her.” He leaped to his feet and slid the pieces of meat along the wire until they were clear of the fire. He took Muley’s knife and sawed through a piece of meat until it was free of the wire. “Here’s for the preacher,” he said.

“I tol’ you I ain’t no preacher.”

“Well, here’s for the man, then.” He cut off another piece. “Here, Muley, if you ain’t too goddamn upset to eat. This here’s jackrabbit. Tougher’n a bull-bitch.” He sat back and clamped his long teeth on the meat and tore out a great bite and chewed it. “Jesus Christ! Hear her crunch!” And he tore out another bite ravenously.

Muley still sat regarding his meat. “Maybe I oughtn’ to a-talked like that,” he said.

“Fella should maybe keep stuff like that in his head.”

Casy looked over, his mouth full of rabbit. He chewed, and his muscled throat convulsed in swallowing. “Yes, you should talk,” he said. “Sometimes a sad man can talk the sadness right out through his mouth. Sometimes a killin’ man can talk the murder right out of his mouth an’ not do no murder. You done right. Don’t you kill nobody if you can help it.” And he bit out another hunk of rabbit. Joad tossed the bones in the fire and jumped up and cut more off the wire. Muley was eating slowly now, and his nervous little eyes went from one to the other of his companions. Joad ate scowling like an animal, and a ring of grease formed around his mouth.

For a long time Muley looked at him, almost timidly. He put down the hand that held the meat. “Tommy,” he said.

Joad looked up and did not stop gnawing the meat. “Yeah?” he said, around a mouthful.

“Tommy, you ain’t mad with me talkin’ about killin’ people? You ain’t huffy, Tom?”

“No,” said Tom. “I ain’t huffy. It’s jus’ somepin that happened.”

“Ever’body knowed it was no fault of yours,” said Muley. “Ol’ man Turnbull said he was gonna get you when ya come out. Says nobody can kill one a his boys. All the folks hereabouts talked him outa it, though.”

“We was drunk,” Joad said softly. “Drunk at a dance. I don’ know how she started.

An’ then I felt that knife go in me, an’ that sobered me up. Fust thing I see is Herb comin’ for me again with his knife. They was this here shovel leanin’ against the schoolhouse, so I grabbed it an’ smacked ’im over the head. I never had nothing against Herb. He was a nice fella. Come a-bullin’ after my sister Rosasharn when he was a little fella. No, I liked Herb.”

“Well, ever’body tol’ his pa that, an’ finally cooled ’im down. Somebody says they’s Hatfield blood on his mother’s side in ol’ Turnbull, an’ he’s got to live up to it. I don’t know about that. Him an’ his folks went on to California six months ago.”

Joad took the last of the rabbit from the wire and passed it around. He settled back and ate more slowly now, chewed evenly, and wiped the grease from his mouth with his sleeve. And his eyes, dark and half closed, brooded as he looked into the dying fire.

“Ever’body’s goin’ west,” he said. “I got me a parole to keep. Can’t leave the state.”

“Parole?” Muley asked. “I heard about them. How do they work?”

“Well, I got out early, three years early. They’s stuff I gotta do, or they send me back in. Got to report ever’ so often.”

“How they treat ya there in McAlester? My woman’s cousin was in McAlester an’ they give him hell.”

“It ain’t so bad,” said Joad. “Like ever’place else. They give ya hell if ya raise hell.

You get along O.K. les’ some guard gets it in for ya. Then you catch plenty hell. I got along O.K. Minded my own business, like any guy would. I learned to write nice as hell.

Birds an’ stuff like that, too; not just word writin’. My ol’ man’ll be sore when he sees me whip out a bird in one stroke. Pa’s gonna be mad when he sees me do that. He don’t like no fancy stuff like that. He don’t even like word writin’. Kinda scares ’im, I guess.

Ever’ time Pa seen writin’, somebody took somepin away from ’im.”

“They didn’ give you no beatin’s or nothin’ like that?”

“No, I jus’ tended my own affairs. ’Course you get goddamn good an’ sick a-doin’ the same thing day after day for four years. If you done somepin you was ashamed of, you might think about that. But, hell, if I seen Herb Turnbull comin’ for me with a knife right now, I’d squash him down with a shovel again.”

“Anybody would,” said Muley. The preacher stared into the fire, and his high forehead was white in the settling dark. The flash of little flames picked out the cords of his neck. His hands, clasped about his knees, were busy pulling knuckles.

Joad threw the last bones into the fire and licked his fingers and then wiped them on his pants. He stood up and brought the bottle of water from the porch, took a sparing drink, and passed the bottle before he sat down again. He went on, “The thing that give me the mos’ trouble was, it didn’ make no sense. You don’t look for no sense when lightnin’ kills a cow, or it comes up a flood. That’s jus’ the way things is. But when a bunch of men take an’ lock you up four years, it ought to have some meaning. Men is supposed to think things out. Here they put me in, an’ keep me an’ feed me four years.

That ought to either make me so I won’t do her again or else punish me so I’ll be afraid to do her again”—he paused—“but if Herb or anybody else come for me, I’d do her

again. Do her before I could figure her out. Specially if I was drunk. That sort of senselessness kind a worries a man.”

Muley observed, “Judge says he give you a light sentence ’cause it wasn’t all your fault.”

Joad said, “They’s a guy in McAlester—lifer. He studies all the time. He’s sec’etary of the warden—writes the warden’s letters an’ stuff like that. Well, he’s one hell of a bright guy an’ reads law an’ all stuff like that. Well, I talked to him one time about her, ’cause he reads so much stuff. An’ he says it don’t do no good to read books. Says he’s read ever’thing about prisons now, an’ in the old times; an’ he says she makes less sense to him now than she did before he starts readin’. He says it’s a thing that started way to hell an’ gone back, an’ nobody seems to be able to stop her, an’ nobody got sense enough to change her. He says for God’s sake don’t read about her because he says for one thing you’ll jus’ get messed up worse, an’ for another you won’t have no respect for the guys that work the gover’ments.”

“I ain’t got a hell of a lot of respec’ for ’em now,” said Muley. “On’y kind a gover’ment we got that leans on us fellas is the ‘safe margin a profit.’ There’s one thing that got me stumped, an’ that’s Willy Feeley—drivin’ that cat’, an’ gonna be a straw boss on lan’ his own folks used to farm. That worries me. I can see how a fella might come from some other place an’ not know no better, but Willy belongs. Worried me so I went up to ’im and ast ’im. Right off he got mad. ‘I got two little kids,’ he says. ‘I got a wife an’ my wife’s mother. Them people got to eat.’ Gets madder’n hell. ‘Fust an’ on’y thing I got to think about is my own folks,’ he says. ‘What happens to other folks is their look- out,’ he says. Seems like he’s ’shamed, so he gets mad.”

Jim Casy had been staring at the dying fire, and his eyes had grown wider and his neck muscles stood higher. Suddenly he cried, “I got her! If ever a man got a dose of the sperit, I got her! Got her all of a flash!” He jumped to his feet and paced back and forth, his head swinging. “Had a tent one time. Drawed as much as five hundred people ever’ night. That’s before either you fellas seen me.” He stopped and faced them. “Ever notice I never took no collections when I was preachin’ out here to folks—in barns an’ in the open?”

“By God, you never,” said Muley. “People around here got so use’ to not givin’ you money they got to bein’ a little mad when some other preacher come along an’ passed the hat. Yes, sir!”

“I took somepin to eat,” said Casy. “I took a pair a pants when mine was wore out, an’ a ol’ pair a shoes when I was walkin’ through to the groun’, but it wasn’t like when I had the tent. Some days there I’d take in ten or twenty dollars. Wasn’t happy that-a-way, so I give her up, an’ for a time I was happy. I think I got her now. I don’ know if I can say her. I guess I won’t try to say her—but maybe there’s a place for a preacher. Maybe I can preach again. Folks out lonely on the road, folks with no lan’, no home to go to.

They got to have some kind of home. Maybe—” He stood over the fire. The hundred muscles of his neck stood out in high relief, and the firelight went deep into his eyes and ignited red embers. He stood and looked at the fire, his face tense as though he were listening, and the hands that had been active to pick, to handle, to throw ideas, grew

quiet, and in a moment crept into his pockets. The bats flittered in and out of the dull firelight, and the soft watery burble of a night hawk came from across the fields.

Tom reached quietly into his pocket and brought out his tobacco, and he rolled a cigarette slowly and looked over it at the coals while he worked. He ignored the whole speech of the preacher, as though it were some private thing that should not be inspected.

He said, “Night after night in my bunk I figgered how she’d be when I come home again.

I figgered maybe Grampa or Granma’d be dead, an’ maybe there’d be some new kids.

Maybe Pa’d not be so tough. Maybe Ma’d set back a little an’ let Rosasharn do the work.

I knowed it wouldn’t be the same as it was. Well, we’ll sleep here I guess, an’ come daylight we’ll get on to Uncle John’s. Leastwise I will. You think you’re comin’ along, Casy?”

The preacher still stood looking into the coals. He said slowly, “Yeah, I’m goin’ with you. An’ when your folks start out on the road I’m goin’ with them. An’ where folks are on the road, I’m gonna be with them.”

“You’re welcome,” said Joad. “Ma always favored you. Said you was a preacher to trust. Rosasharn wasn’t growed up then.” He turned his head. “Muley, you gonna walk on over with us?” Muley was looking toward the road over which they had come. “Think you’ll come along, Muley?” Joad repeated.

“Huh? No. I don’t go no place, an’ I don’t leave no place. See that glow over there, jerkin’ up an’ down? That’s prob’ly the super’ntendent of this stretch a cotton.

Somebody maybe seen our fire.”

Tom looked. The glow of light was nearing over the hill. “We ain’t doin’ no harm,” he said. “We’ll jus’ set here. We ain’t doin’ nothin’.”

Muley cackled. “Yeah! We’re doin’ somepin jus’ bein’ here. We’re trespassin’. We can’t stay. They been tryin’ to catch me for two months. Now you look. If that’s a car comin’ we go out in the cotton an’ lay down. Don’t have to go far. Then by God let ’em try to fin’ us! Have to look up an’ down ever’ row. Jus’ keep your head down.”

Joad demanded, “What’s come over you, Muley? You wasn’t never no run-an’-hide fella. You was mean.”

Muley watched the approaching lights. “Yeah!” he said. “I was mean like a wolf.

Now I’m mean like a weasel. When you’re huntin’ somepin you’re a hunter, an’ you’re strong. Can’t nobody beat a hunter. But when you get hunted—that’s different. Somepin happens to you. You ain’t strong; maybe you’re fierce, but you ain’t strong. I been hunted now for a long time. I ain’t a hunter no more. I’d maybe shoot a fella in the dark, but I don’t maul nobody with a fence stake no more. It don’t do no good to fool you or me.

That’s how it is.”

“Well, you go out an’ hide,” said Joad. “Leave me an’ Casy tell these bastards a few things.” The beam of light was closer now, and it bounced into the sky and then disappeared, and then bounced up again. All three men watched.

Muley said, “There’s one more thing about bein’ hunted. You get to thinkin’ about all the dangerous things. If you’re huntin’ you don’t think about ’em, an’ you ain’t scared.

Like you says to me, if you get in any trouble they’ll sen’ you back to McAlester to finish your time.”

“That’s right,” said Joad. “That’s what they tol’ me, but settin’ here restin’ or sleepin’ on the groun’—that ain’t gettin’ in no trouble. That ain’t doin’ nothin’ wrong. That ain’t like gettin’ drunk or raisin’ hell.”

Muley laughed. “You’ll see. You jus’ set here, an’ the car’ll come. Maybe it’s Willy Feeley, an’ Willy’s a deputy sheriff now. ‘What you doin’ trespassin’ here?’ Willy says.

Well, you always did know Willy was full a crap, so you says, ‘What’s it to you?’ Willy gets mad an’ says, ‘You get off or I’ll take you in.’ An’ you ain’t gonna let no Feeley push you aroun’ ’cause he’s mad an’ scared. He’s made a bluff an’ he got to go on with it, an’ here’s you gettin’ tough an’ you got to go through—oh, hell, it’s a lot easier to lay out in the cotton an’ let ’em look. It’s more fun, too, ’cause they’re mad an’ can’t do nothin’, an’ you’re out there a-laughin’ at ’em. But you jus’ talk to Willy or any boss, an’ you slug hell out of ’em an’ they’ll take you in an’ run you back to McAlester for three years.”

“You’re talkin’ sense,” said Joad. “Ever’ word you say is sense. But, Jesus, I hate to get pushed around! I lots rather take a sock at Willy.”

“He got a gun,” said Muley. “He’ll use it ’cause he’s a deputy. Then he either got to kill you or you got to get his gun away an’ kill him. Come on, Tommy. You can easy tell yourself you’re foolin’ them lyin’ out like that. An’ it all just amounts to what you tell yourself.” The strong lights angled up into the sky now, and the even drone of a motor could be heard. “Come on, Tommy. Don’t have to go far, jus’ fourteen-fifteen rows over, an’ we can watch what they do.”

Tom got to his feet. “By God, you’re right!” he said. “I ain’t got a thing in the worl’ to win, no matter how it comes out.”

“Come on, then, over this way.” Muley moved around the house and out into the cotton field about fifty yards. “This is good,” he said, “Now lay down. You on’y got to pull your head down if they start the spotlight goin’. It’s kinda fun.” The three men stretched out at full length and propped themselves on their elbows. Muley sprang up and ran toward the house, and in a few moments he came back and threw a bundle of coats and shoes down. “They’d of taken ’em along just to get even,” he said. The lights topped the rise and bore down on the house.

Joad asked, “Won’t they come out here with flashlights an’ look aroun’ for us? I wisht I had a stick.”

Muley giggled. “No, they won’t. I tol’ you I’m mean like a weasel. Willy done that one night an’ I clipped ’im from behint with a fence stake. Knocked him colder’n a wedge. He tol’ later how five guys come at him.”

The car drew up to the house and a spotlight snapped on. “Duck,” said Muley. The bar of cold white light swung over their heads and criss-crossed the field. The hiding men could not see any movement, but they heard a car door slam and they heard voices.

“Scairt to get in the light,” Muley whispered. “Once-twice I’ve took a shot at the headlights. That keeps Willy careful. He got somebody with ’im tonight.” They heard footsteps on wood, and then from inside the house they saw the glow of a flashlight.

“Shall I shoot through the house?” Muley whispered. “They couldn’t see where it come

from. Give ’em somepin to think about.”

“Sure, go ahead,” said Joad.

“Don’t do it,” Casy whispered. “It won’t do no good. Jus’ a waste. We got to get thinkin’ about doin’ stuff that means somepin.”

A scratching sound came from near the house. “Puttin’ out the fire,” Muley whispered. “Kickin’ dust over it.” The car doors slammed, the headlights swung around and faced the road again. “Now duck!” said Muley. They dropped their heads and the spotlight swept over them and crossed and recrossed the cotton field, and then the car started and slipped away and topped the rise and disappeared.

Muley sat up. “Willy always tries that las’ flash. He done it so often I can time ’im.

An’ he still thinks it’s cute.”

Casy said, “Maybe they left some fellas at the house. They’d catch us when we come back.”

“Maybe. You fellas wait here. I know this game.” He walked quietly away, and only a slight crunching of clods could be heard from his passage. The two waiting men tried to hear him, but he had gone. In a moment he called from the house, “They didn’t leave nobody. Come on back.” Casey and Joad struggled up and walked back toward the black bulk of the house. Muley met them near the smoking dust pile which had been their fire.

“I didn’ think they’d leave nobody,” he said proudly. “Me knockin’ Willy over an’ takin’ a shot at the lights once-twice keeps ’em careful. They ain’t sure who it is, an’ I ain’t gonna let ’em catch me. I don’t sleep near no house. If you fellas wanta come along, I’ll show you where to sleep, where there ain’t nobody gonna stumble over ya.”

“Lead off,” said Joad. “We’ll folla you. I never thought I’d be hidin’ out on my old man’s place.”

Muley set off across the fields, and Joad and Casy followed him. They kicked the cotton plants as they went. “You’ll be hidin’ from lots of stuff,” said Muley. They marched in single file across the fields. They came to a water-cut and slid easily down to the bottom of it.

“By God, I bet I know,” cried Joad. “Is it a cave in the bank?”

“That’s right. How’d you know?”

“I dug her,” said Joad. “Me an’ my brother Noah dug her. Lookin’ for gold we says we was, but we was jus’ diggin’ caves like kids always does.” The walls of the water-cut were above their heads now. “Ought to be pretty close,” said Joad. “Seems to me I remember her pretty close.”

Muley said, “I’ve covered her with bresh. Nobody couldn’t find her.” The bottom of the gulch leveled off, and the footing was sand.

Joad settled himself on the clean sand. “I ain’t gonna sleep in no cave,” he said. “I’m gonna sleep right here.” He rolled his coat and put it under his head.

Muley pulled at the covering brush and crawled into his cave. “I like it in here,” he called. “I feel like nobody can come at me.”

Jim Casy sat down on the sand beside Joad.

“Get some sleep,” said Joad. “We’ll start for Uncle John’s at daybreak.”

“I ain’t sleepin’,” said Casy. “I got too much to puzzle with.” He drew up his feet and clasped his legs. He threw back his head and looked at the sharp stars. Joad yawned and brought one hand back under his head. They were silent, and gradually the skittering life of the ground, of holes and burrows, of the brush, began again; the gophers moved, and the rabbits crept to green things, the mice scampered over clods, and the winged hunters moved soundlessly overhead.